Written for Theatre Bubble, March 2016

Wagner’s original Ring Cycle, which forms the content for the majority of the Unexpected Opera Company’s latest show at the Charing Cross Theatre (here the Rinse Cycle (gettit?), was originally a series of four epic music dramas – each meant to be performed over consecutive nights to give the performers (and the audience) something more than an intense 16 hour musical experience. Here, typical for the launderette setting, these four operas have been stuffed into a two hour time slot, scented with a sweet charm, and left to spin in a merry and hectic stage experience.

The five performers, each operatically trained and incredibly talented, all acquitted themselves marvellously. Alongside the performance of Wagner’s score came a metatheatrical series of romantic capers between the characters themselves. It certainly took a while to adjust to this structure and form, but it worked a treat. Though clearly their acting took second billing to their singing, the five created a wonderful and hilarious experience for the audience. It’d be unjust to single any of them out.

This was not a show for Wagner purists, as the characters frequently had to provide quick exposition and witty barbs to make sure that the whole plot was dealt with quickly and effectively. Overall the tone of the show seemed to pitch itself somewhere between Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra (with actors often breaking off to explain leitmotifs or comment on how similar the narrative is to that of Tolkien), Michael Frayn’s Noises Off (with its equally ludicrous backstage farce), and the recent production of Jurassic Park at the Edinburgh Fringe. There were enough sex gags to shake a conductor’s baton at.

True, some of the jokes were cringe-worthily borderline racist and a couple of the characters seemed entirely two-dimensional, but what was most important was that this mattered so little – Unexpected Opera have created a merry night of exceptionally talented performers having a chance to take their material and do something different with it. The low-budget dragon or plastic helmets could be forgiven in an instant. After a near-incomprehensible ending to the meta-narrative and a good old sing-a-long, the audience (and this reviewer included) mostly left the audience beaming.

Credit must also go to the pianist, who tackled Wagner’s score with panache and delicacy – the music was stripped down to its most necessary motifs and functions, whilst leaving opportunity for some wonderful harmonies and moments to really show the composer’s finesse. Wagner really likes to get the most out of his orchestra during his operas, and showing that range of tone and timbre on a single piano was done perfectly.

It took a while to gel with the Rinse Cycle, but what emerged was a fantastically heartwarming and endearing show. Don’t miss it whilst it’s on at the Charing Cross Theatre!

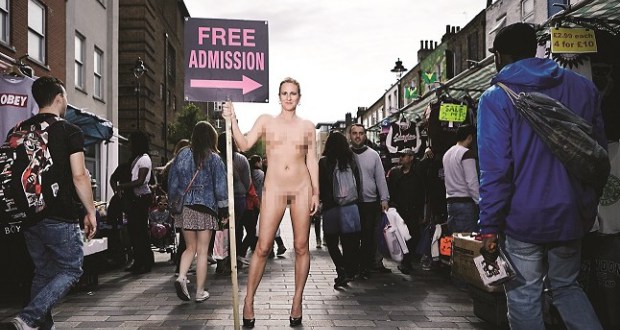

Photo by Robert Workman

The bluntness of the bed-drop scene change is far more symbolic than perhaps intended. With this huge transformation in tone that Firebird betrays a problem – writing that had formerly been laced with subtlety and charm is instead rendered blunt, uncompromising and exhausting.

The bluntness of the bed-drop scene change is far more symbolic than perhaps intended. With this huge transformation in tone that Firebird betrays a problem – writing that had formerly been laced with subtlety and charm is instead rendered blunt, uncompromising and exhausting.